You never know where the winds of interest will blow the writing fires. I have reveled in the vast lands of nonfiction most of my writing life, but I’ve also braved the world of novels, short stories, plays, and poetry as well. Lately, I have entered an area in which I have always had interest: screen writing.

This is not my first experience with this type of writing. Years back, I took a screenwriting class, got enthused, and wrote a few Seinfeld scripts that landed me an agent but no sales. “It’s written in-house,” the agent told me. “If you want to write scripts, write an original screenplay (= movie).”

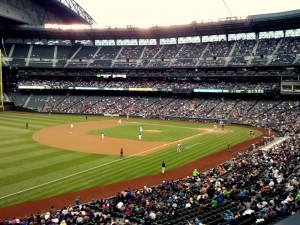

I grumbled, groused, and then moved on to other projects that excited me. Years passed, and then one day I was in Seattle, visiting a friend and viewing a few Mariner baseball games. As usual during that time, the Mariners were not doing too well and the papers reported that the team was considering firing their manager.

What if? I thought. What if they decided to hire a nonprofessional—just a regular guy who coached kids—to finish out the season? And what if this guy was having challenges of his own at the time?

These questions became the seeds for my story, and the tagline (every movie has one) became “A man takes on baseball. And himself.”

I thought about this for a year, and for the past six months I have worked at trying to transport it from my head to paper. Along the way I have read books on the craft (including the technical aspects of the genre), read other screenplays, watched lots of movies, and took copious notes.

What I enjoyed was the spare nature of the writing: it’s mostly dialogue and some directions, but little room for description. That also makes it challenging, too. Descriptions help you create context and make smooth transitions.

Last week I finished the first draft, one hundred fifteen pages of it. Like every first draft I have ever done, there was relief involved, relief that the story had held together to its conclusion. Is the story any good? I don’t know. Really, I don’t. I have printed it out and set it aside. At some point in time—a week, a month, five years—I’ll return to the script, this time with fresh eyes and I’ll read it.

And then I’ll get to work, the real work, of rewriting it. How long will that take? I don’t have a clue. A couple weeks. A month. A year. As long as it takes, until I’m satisfied.

And then what? Then, I’ll try to find a home for it, a home where the script can be made into a movie. This will be a daunting task, indeed, and the odds will be long. Maybe not as long as singing at the Met or batting cleanup for the Orioles, but the chances of my script ever being made into a movie are slim.

So, why take the time to work on such a project in the first place, when the odds are clearly against you and where other avenues of writing provide you with a much better chance for success? The answer is simple: You never know. You just never know.